Robert Nye,“The Culture of the Sword: Manliness and Fencing in the Third Republic” from Masculinity and Male Codes of Honor in Modern France (2)

The Roots of Honor in 19th Century France

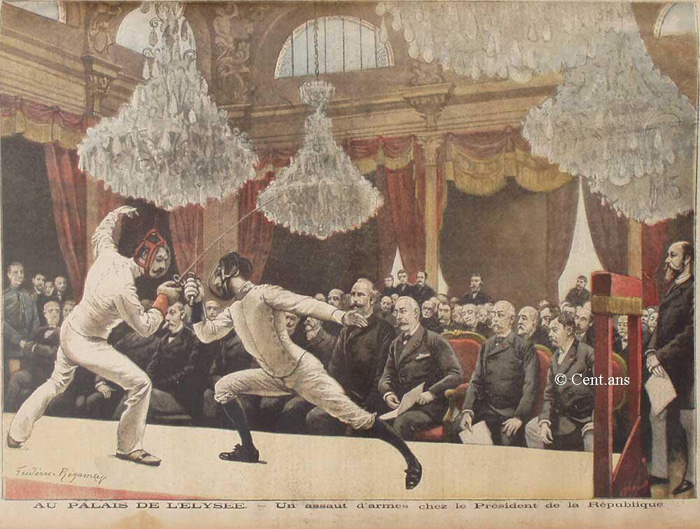

"At the Elysee Palace -- A Show of Arms at the President of the Republic," Petit Journal (1895)

In France, paradoxically, the glorification of chivalry was to a remarkable extent the work of liberal [in the European context the word liberal refers to someone who is pro-business, supports limited democracy, and opposses government intervention in the economy] and progressive thinkers. In the hands of an early nineteenth-century liberal intellectual like the historian-politician Francois Guizot, the rediscovery of the "moral" component in medieval life had both a political and a patriotic significance. First, it allowed bourgeois thinkers of the post-revolutionary era to praise the parts of France's royalist past that had shaped French civilization but that transcended the monarchy itself, in order to prove, as Stanley Mellon has said, that "France of the Revolution need not be ashamed of the Old Regime and that the Revolution had been wrong to despise the French past." 10 By employing a discourse of chivalry, liberals could celebrate a richer and deeper moral heritage than could be derived from the egoistic doctrines of liberal economics and legal individualism, but they could also present themselves and their politics of the juste milieu as lying somewhere between the extremes of royalist tyranny and revolutionary anarchy.

Second, by identifying with chivalry, which Guizot (after the example of Tacitus) believed had descended from the military rites of the ancient Germanic tribes, liberals were able to appropriate for themselves the quality of courage in the warrior ethic that was the irreducible core of the French patriotic tradition. As Leon Gautier, the foremost nineteenth century historian of chivalry, expressed it in 1884, we are fortunate that the "French race . . . still loves the fatherland," since there are still many Frenchmen who "know and practice all the delicacies of honor and prefer death to the felony of a single lie."11

In his "History of Civilization in France," which he first presented in his Sorbonne lectures of 1828-30, Guizot disparaged the social heritage of feudal chivalry, but praised its moral nature, which made medieval life "appear beautiful and pure amidst the licentiousness and grossness of actions." 12 In Guizot's account, the efflorescence of chivalry in the early Middle Ages made seigneurs both valorous and courteous in dealings withtheir fellow nobles and civilized relations between husband and wife within the castle walls. In his words, "There is no one but knows that the domestic life, the spirit of family, and particularly the condition of women, were developed in modern Europe much more completely than elsewhere." 13

In his description of France's chivalric past, Guizot articulated a body of interlocking ideals that remained central to the value system of the French bourgeoisie for the remainder of the century. It is tempting to contrast this bookish syncretism unfavorably with the genuine aristocratizing activity of the Old Regime bourgeoisie, but this would risk overlooking how successfully chivalric ideals expressed the practical aims of the French bourgeoisie at virtually each moment of its development. Chivalry was by no means inconsistent with the middle-class work ethic or with political and civic egalitarianism; a rhetoric of knightly honor also permitted bourgeois males the luxury of thinking themselves to be men of courage and the protectors of women and the weak.